Sitting in one of the university lecture halls, eyes wide open, I crouched forward placing all my efforts to consume every single word uttered by the lecturer who was introducing us students to a new way of understanding disability. The explanation provided was promptly broken down into fragments, incessantly trying to place order in my brain by integrating the meaning of the reasoning that was being provided. Suddenly it felt like something clicked, a rush of adrenaline pushed through my veins, I jumped and squiggled on my seat… “ AAAHAAA… That’s it! Yes! How could I not think of disability in this way before?”

Disability is a subject that I hold close to my heart and for a very good reason. My 15 year old daughter is on the Autism Spectrum, a condition that presents her with challenges in her social interaction, speech and nonverbal communication. Raising my daughter I have vicariously experienced the stigma and discrimination associated with disability, and for many years I have struggled to understand it and make sense out of it. Why are these kids pushed to the periphery of classes or even worse expected to spend most of the time out of class? How can school staff decide to send these kids back home if their LSE does not show up for work? Why are these kids not invited to birthday parties like their peers? And why on earth are they not accepted in extra-curricular activities like sports and art classes after school hours that can provide them with a sense of belonging?

The content of this lecture helped me place order to these baffling thoughts and hopefully it will help other mothers who like me might be struggling to understand the unfortunate discriminative processes taking place around individuals with disability.

Models of Disability

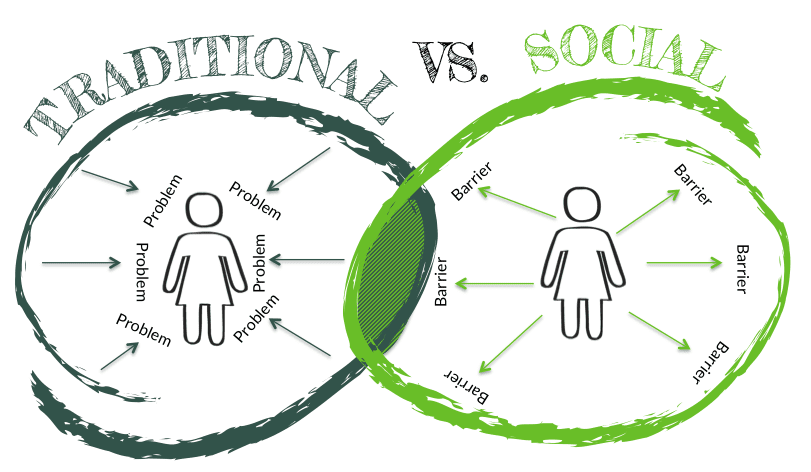

Disability studies utilise a variety of models to enlighten people’s understanding of the multidimensional characteristics surrounding disability. Models of disability have been vital tools in the past 40 years, informing disability politics, disability studies and human rights for people with disability. Models have the potential to impart the way people look at particular aspects of reality, by revealing underlying abstract systems and convoluted societal processes which might not be readily understood by the lay person.

Therefore, one of the aims of a good model of disability is to leave an impact on social policy and provoke social change (Brett, 2002), providing society with an alternative lens to look at disability and generating novel explanations of the phenomenon. However models of disability are not merely simple definitions, they operate as analytical tools divulging various aspects associated to disability such as the uncovering of embedded ideologies within society (Smart, 2009). As a consequence shaping psychological, political, and economic outcomes associated with disability (Dirth & Branscombe, 2017).

The Medical Model of Disability

Historically, the role of disseminating a definition of disability to society was transferred from religious leaders, over to scientific or medical professionals who held, and still retain considerable amount of “cognitive authority” over how the concept of disability is understood by society (Brittain, 2004). This representational shift took place during the early twentieth century, from one that viewed people with disability as objects of charity, to one that sees them as having something inherently wrong (Oliver, 1996). Barton (2009), states that these definitions and the discourse used to describe this minority group, is critical in shaping society’s expectations and interactions with people with disabilities.

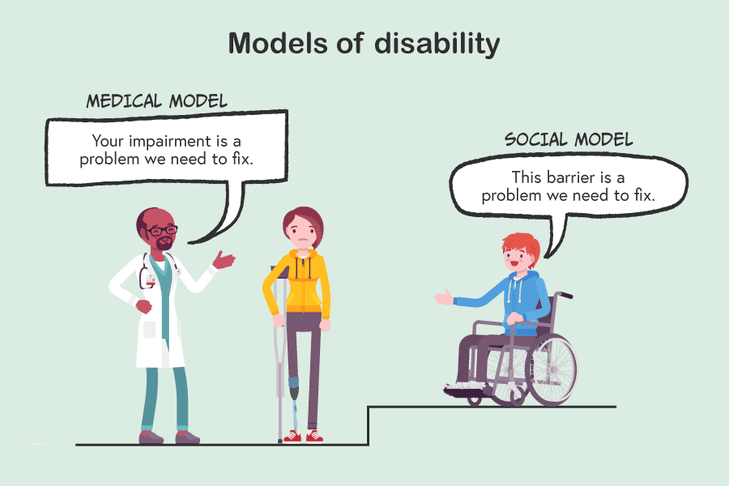

The Medical Model views disability from a biological and pathological perspective, focusing the spotlight on the functional or cognitive limitations of the person (Cameron, 2014). It’s aim is to diagnose and subsequently treat or cure the broken body or mind that deviates from society’s view of “normality” . When a person is viewed as not fitting the norms of society he or she is propelled into a stigmatizing status (Goffman, 1963). The person who carries the stamp of stigma undergoes status loss, is disqualified from social acceptance and suffers discrimination and power-imbalances (Link & Phelan, 2001). The moment a person is perceived as being impaired, a mechanism of social oppression is put into motion, ostracising the deviant person from the rest of the group. The repercussions of stigma in a small community like Malta can have overbearing consequences on the person with disability, who might face added difficulties to fit in.

The focus on impairment and the unrelenting obsession to fix the person can have deleterious consequences on this vulnerable group. These negative outcomes are further aggravated by the tendency of utilizing the medical model in the film industry, literature and the media in general, projecting an unabating sick role on this group, reinforcing a negative perception within society, and portraying this group in a stigmatizing and pitiful way. Such conceptualisations denote a concept of tragedy around disability that needs to be surmounted or fixed at all costs, providing no solace whatsoever to citizens whose disability is a part of their daily reality (Marks, 1997).

The Social Model

The Social Model of Disability provides us with an alternative way to look at disability, unravelling the underlying injustices that linger in society’s ideology surrounding disability. It claims that the major obstacles that stifle the person with disability from developing into a fully-fledged citizen is not their impairment per se, but a discriminating society that fails to compensate for their disability (Oliver, 1990).

The Social Model provides a clear distinction between the words impairment and disability, throwing light on our understanding of how disability emanates from social organisations that dismiss the needs of people with physical and cognitive impairments (Oliver, 1990). Thus disability within the social model framework is seen as being inflicted on the person with impairment, rather than intrinsically found within the person. Society is viewed as prohibiting people with impairments to attain an equitable place in their community, since they are denied the opportunity to participate actively within society. By comprehending disability from this lens, a realisation of the extent of physical and attitudinal barriers that society imposes upon people with disability becomes palpable. This model offers an alternative way of viewing disability and formulating solutions, aiming at fixing the organisation and structure of a dysfunctional society, instead of expecting the person with disability to adjust to his or her environment.

Despite the fact that the prevalence of the social model within disability study research is unquestionable, a number of professionals working within the disability field still hold a generally individualistic view of disability. This has been documented by Callus (2013) in a local study on people with intellectual disability, who concluded that “environmental factors play a much more important part in the lives of people with intellectual disability than any innate impairment they may possess”. Such findings point towards a dominant representation of disability within Maltese culture which persists in locating the disability within the individual.

Battling disablism

Over the past years my experience with disability has made me come to the realisation that no amount of wealth, legislation and social benefits will allow my daughter to enjoy equal human rights in the same way they are experienced by people without disability. The plain truth is that what my daughter needs is an accepting society that possesses the ability to look beyond her autism, celebrate her capabilities, share her joys and acknowledge her difficulties.

If we want to leave behind a more habitable and humane world for our children we need to nurture and advocate for a more emphatic society that is able to acknowledge with respect these diverse ways being in the world. Battling disablism however is not an easy undertaking and will require the moral courage of individuals with disability and their significant others to share their stories in order to become visible and create impactful awareness that ignites change.

“Our ability to reach unity in diversity will be the beauty and the test of our civilization”

Mahatma Gandhi

References

Barton, L. (2009). Disability, physical education and sport: Some critical observations and questions. In H. Fitzgerald (Ed.), Disability and youth sport (pp. 39–50). New York, NY: Routledge.

Brett, J. (2002). The Experience of Disability from the Perspective of Parents of Children with Profound Impairment: Is it time for an alternative model of disability? Disability & Society, 17(7), 825-843.

Brittain, I. (2004). Perceptions of Disability and their Impact upon Involvement in Sport for People with Disabilities at all Levels. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 28(4), 429-452.

Callus, A. (2013). Becoming self-advocates: People with intellectual disability seeking a voice. Oxford: Peter Lang.

Cameron, C. (2010) Does Anybody Like Being Disabled? A Critical Exploration of Impairment, Identity, Media and Everyday Experience in a Disabling Society, PhD thesis, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh.

Dirth, T. P., & Branscombe, N. R. (2017). Disability Models Affect Disability Policy Support through Awareness of Structural Discrimination. Journal of Social Issues, 73(2), 413-442

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster

Link, B. & Phelan, J. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review Of Sociology, 27, 363-385.

Marks, D. (1997). Models of disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 19(3), 85-91.

Oliver, M. (1990) The Politics of Disablement. Basingstoke. Macmillan.

Oliver, M. (1996). Understanding disability: From theory to practice. Basingstoke, England: Macmillan.

Smart, J. F. (2009). The power of models of disability. Journal of Rehabilitation, 75(2), 3–11.

Do you have an experience with regards to understanding disability that you’d like to share with us at wham? Contact us or send us an email at [email protected]